The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has taken on mythical proportions over the years, with its praises sung so frequently and its detriments so understated that most Americans don’t even question its utility. Its very popularity naturally encourages people not to question it. And that continues to be a problem.

In Part 1, we discussed the drawbacks of the TYFRM for borrowers, with the most notable red flags being the significant increase in interest borrowers pay to have the option to prepay and the painfully slow accumulation of equity that can hurt borrowers in an economic downturn (and flies in the face of the notion of homeownership is a fast track to build wealth).

Today, we’re going to consider the TYFRM from the lender and investor point-of-view.

The inherent risk built into the 30-year mortgage

As a mortgage product, when you actually dig into the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, it doesn’t make a ton of sense for lenders or investors. After all, as we discussed in Part 1, the long-term nature of the product is cheaper for borrowers but the development of the HOLC, as well as Fannie and Freddie, was at least partially influenced to incentivize lenders to offer these longer-term loan products promoted by the FHA in post-war America.

Financial institutions are safest when characteristics of their assets match the characteristics of their obligations. For example, a company in the business of selling 10-year fixed annuities would want to back those annuities with 10-year fixed-rate assets.

Let’s put on our fixed-income investor cap (a newly acquired hat for me personally) for a moment.** If you’re a fixed-income investor, you buy bonds and care about their yield, but you also care about their duration. Duration refers to both the measure of the weighted average time that the investor receives cash flow, as well as the asset’s sensitivity to interest rate change. The longer the asset’s term, the more sensitive it is to rate changes.

Many fixed-income investors have quantifiable liabilities that also have an expected duration: they know the approximate average date that their fund pays out, and if interest rates fall, the present value of their liabilities would go up. Thus, an investor might run a duration-hedge strategy so that the duration of their liabilities (we’ll say seven years in this example) would be matched with assets of a similar duration so that any interest rate changes affect their assets and liabilities in equal measure.

Stay with me, I swear it gets easier from here.

But mortgages are weird, and the mortgage prepayment option has a strange impact on duration in that when interest rates decline, more mortgages get repaid, and so the duration declines. In other words, the duration of a mortgage changes with market conditions in a way that is adverse to the lender.

So, to continue the above example, if you’re an investor with liabilities with a seven-year duration and you also own agency securities (i.e. mortgage-backed securities issued by Fannie and Freddie), when interest rates fall, the value of your liabilities and the value of your fixed-income assets are raised — with the exception of mortgages. The mortgages get paid down at 100 cents on the dollar and now your assets are less sensitive to rate changes, just when you were starting to benefit.

The same is true in the opposite direction: when rates rise, people have an incentive to defer moving and thus duration increases and the value of fixed-income assets declines, so investors are again getting the short end of the stick. So the odd behavior of mortgage investments almost counteract the momentum of your other assets and liabilities as interest rates change.

This is why investors in mortgage-backed securities demand higher interest rates on 30-year mortgages, and it goes back to the prepayment penalty: because borrower get the option to refinance without penalty (which is bad for investors), borrowers essentially pay much more in interest over the life of their loan to compensate for this.

All of this to say that investors are not naturally predisposed to hold 30-year fixed-rate assets to maturity; instead, they invest in mortgages to earn a return for a few months or years and then may sell it off to offload the risk.

This is why complex financial tools like interest-rate options, swaps, and other complex derivatives pop up in the mortgage finance space.

Investors need to balance their portfolio against the interest-rate risk built into the mortgage market by the longer-term fixed-rate mortgage products.

As economist Arnold Kling explains:

“Although any one institution can use sophisticated financial instruments to transfer away the interest-rate risk embedded in mortgages, that risk does not disappear. It ends up somewhere else. Because government officials are loathe to see important financial institutions fail, “somewhere else” all too often ends up being in the hands of the taxpayers.

Interest-rate risk migrates toward those financial institutions that enjoy the highest level of perceived government protection with the least effective form of regulation. The perceived government protection enables them to serve as reliable counterparties to households and firms seeking risk protection. The relatively less stringent regulation leads the risk-bearing institutions to reap gains when interest rates are relatively stable, without having to hold sufficient capital to survive a major shock.”

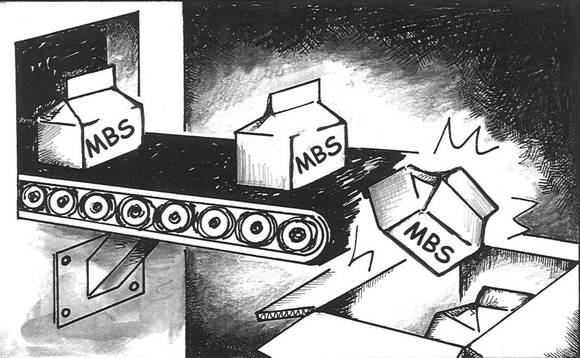

Much of the mortgage market as we know it today as a scramble to offload the interest-rate risk that is created by the long-term fixed-rate mortgage. A mortgage lender doesn’t want to keep it on their books, so they sell it to investors, who then have to hedge that risk.

Interest-rate risk hot potato

Two major historical moments illustrate how dangerous this game of interest-risk hot potato becomes when you combine government securitization and policy initiatives that push for wider use of the TYFRM: the S&L crisis in and the more recent bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac after the recession.

In the decades following World War II, the Savings and Loan (S&L) industry enjoyed the most government protection with little regulatory oversight, and S&Ls loaded up on interest-rate risk, issuing 30-year mortgages funded by deposits that could be instantly liquidated.

As Arnold Kling notes, S&L employees would joke that managing an S&L was “a simple 3-6-3 job: pay savers a rate of 3 percent on deposits, charge borrowers 6 percent on mortgage loans, and go to the golf course at 3 p.m.”

This worked swimmingly as long as short-term interest rates stayed below 6 percent. But in the late 1970s when rates soared beyond 10 percent, S&Ls were suddenly faced with a substantial negative spread from paying 10 percent on liabilities while earning 6 percent on assets.

When interest rates fall, prepayment rates climb, and investors have to reinvest that principal at a new, lower interest rate.

By the late ‘80s, the S&L industry was largely insolvent. The quick fix? Throw $100B (in 1980s dollars!) of taxpayer money at the problem and let the S&Ls grow out of it. After that, bank regulators and S&Ls tightened up capital and account requirements to protect against this interest rate risk.

Suddenly, the path of least regulatory resistance with the luxury of government backing was Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. And thus followed the interest-rate risk.

During the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac similarly suffered losses on their mortgage portfolio at the hands of the soaring rates that decimated the S&Ls but were able to grow their way out of the trouble, assisted by the interest rate decline in the mid-1980s.

Freddie Mac had avoided interest-rate risk in the early ‘80s by selling all of its mortgage loans to investors as securities but by the early 1990s had discovered — inspired by Fannie Mae’s lead — that the most profitable strategy was to retain mortgage securities in their portfolio while taking on and (attempting to) manage interest-rate risk.

But we all know how that story goes. Because both Fannie and Freddie had laughably low capital requirements (their capital requirements was 45 basis points so Fannie and Freddie only needed to hold $450 on their books to guarantee a $100k 30-year mortgage), when homeowners started to cash out their mortgage equity rather than buying new homes before the crash, Fannie and Freddie had to massively write down their mortgage positions and quickly reached insolvency.

So the government offered them a gargantuan line of credit in exchange for the rights to buy about 80% of their shares outstanding and a high-dividend preferred stock, and the government also later changed the terms of this preferred stock to entitle the Treasury to all of Fannie and Freddie’s profits.

As economist Byrne Hobart points out:

“This is an economic structure that doesn’t particularly make sense: Fannie and Freddie are in the business of using the government’s implicit guarantee as a source of cheap capital; they borrow cheaply and lend not-so-cheaply, and pocket the difference — or used to. Now, the US Treasury pockets the difference.

So, economically, what happens is that the US government issues debt, buys mortgages, and turns a profit on the gap. As far as anyone knows, the reason the deal’s legal structure doesn’t match that accounting structure is that Fannie and Freddie have a lot of debt, and the government doesn’t want to consolidate it on their balance sheet. So Fannie and Freddie are a highly-levered off-balance-sheet structured credit play.”

In other words, the structure of the deal to place Fannie and Freddie under government conservatorship was structured so that the buyer (the U.S. government) gets to keep a lot of the risk off of its balance sheet even though, economically, they’re still on the hook for that risk.

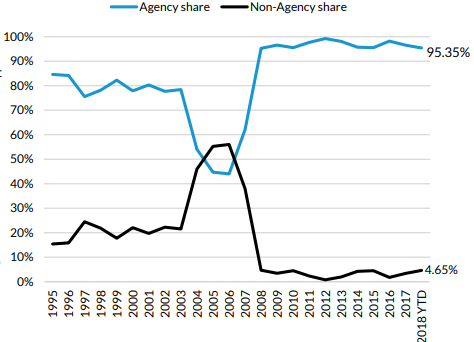

The scariest part of it all is that after the crisis, Fannie and Freddie’s market share in mortgage securitizations went up. Private-label securities went from 42% of the market in 2006 to 1.3% in 2015.

As of 2018, agency debt (i.e. mortgage-backed securities) is up around 95%

And, as Dick Lepre, senior loan advisor for RPM Mortgage points out in Scotsmans Guide, if you got a mortgage after 2011, the higher interest rates or upfront point you experience are basically the price you pay for the GSE’s losses:

“After the crash, Freddie and Fannie lost $187 billion, which was covered by Treasury. After they were put into conservatorship, the GSEs worked to get their house in order and also raised their guarantee fees. Treasury has since recouped the entire $187 billion in losses — and nearly $100 billion more. In essence, everyone who has gotten a loan since 2011 is paying in the form of an increased interest rate or upfront points for the GSE losses and is now making money for Treasury.”

The most important impact of mortgage securitization is that it allows for the 30-year mortgage to flourish. Without a securitization system in place, lenders and investors would have little incentive (in fact, they would be disincentivized) to promote 30-year fixed-rate mortgage terms.

Built-in codependency: a tale of GSE securitization & the 30-year mortgage

The history of the 30-year mortgage is, in many ways, a two-for-one, because the history of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is also, in essence, a history of GSE securitization.

During our mortgage product world tour in Part 2, we established that the United States mortgage market is unique for three reasons:

- We are the only country in the world besides France with a majority preference for long-term fixed-rate mortgages

- We are one of the only countries that does not require prepayment penalties for long-term fixed-rate mortgages

- We are the only country in the world to utilize all three types of government-sponsored institutions (government guarantees, mortgage insurance, and government-sponsored entities).

All three of these anomalies are closely intertwined because the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage would not truly be able to dominate our mortgage market without ongoing government subsidization. Their fates are inextricably linked.

Theoretically, the TYFRM could survive without government subsidization; that’s why there is still a (small) market for 30-year jumbo loans that are too big to be bought by Fannie or Freddie or insured by the FHA. So government backing is not necessarily a prerequisite for a 30-year fixed-rate loan to be plausible.

But the 30-year mortgage would be far less appealing to all parties involved if government securitization was off the table.

The 30-year mortgage isn’t inherently bad, but it’s not such a great deal for homeowners that it should be such a core feature of our housing policy (and one that hinges on taxpayers taking the fall during a crisis).

As Edward Pinto, Director of the AEI Housing Center and former Executive Vice President of Fannie Mae, argues:

“While homeowners can benefit from very long-term FRMs, it is erroneous for federal policy to assume that these mortgage finance instruments will work best for everyone.”

He continues:

“The Housing Lobby unabashedly supports the broad availability of the 30-year mortgage, and even wants it extended to manufactured housing. This is because Housing Lobby sees the slow amortization as a feature that reduces monthly payments, making home ‘more affordable’. They choose to ignore the bug – the 30-year loan, when combined with other risk factors, drives up home prices when the supply of homes is tight, especially for buyers of entry-level homes.”

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is not the best we can get, and much of the discussion around GSE reform presupposes that preserving the golden child of the American mortgage product family is imperative to the integrity of our housing market in America.

Part of the problem is that many Americans have been duped into thinking that low monthly payments equals affordable housing, and that requires a massive leap in logic that continues to hurt us:

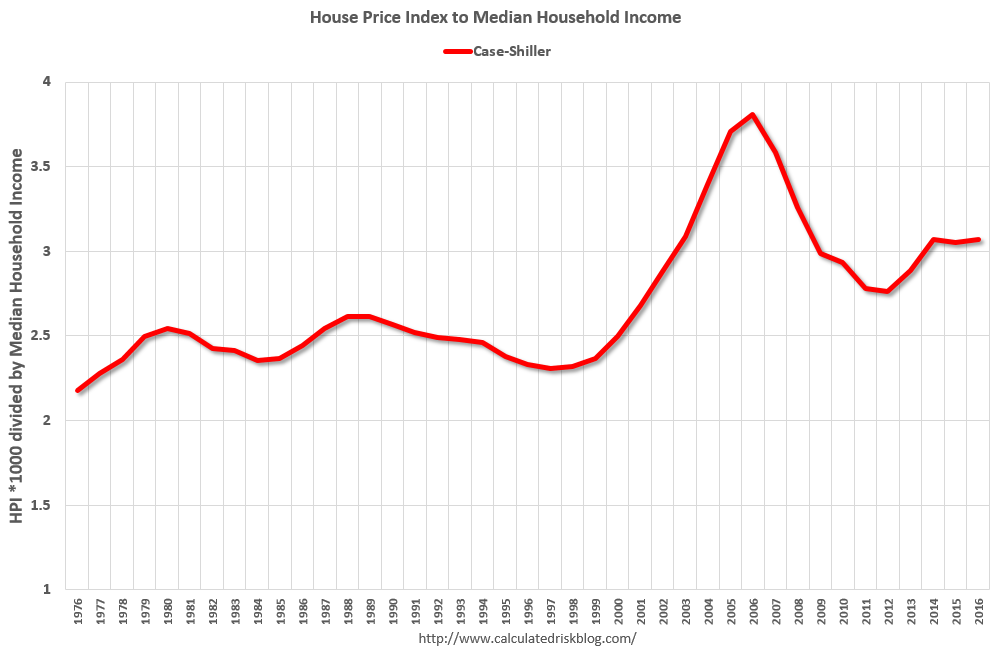

“History has shown that the 30-year’s lower monthly payment does not make homes more affordable. Instead, it leads to faster median home price growth relative to median incomes. Back in the 1950s, before the large-scale adoption of the 30-year loan, the median home price was about 2 times median income. Today, this ratio is over 3.5. This result is predictable, as Ernest Fisher, FHA’s first chief economist in the 1930s and a university professor in the 1950s, observed that in a seller’s market, ‘more liberal credit is likely to be [capitalized] in price.’

As the easy terms of the thirty-year loan gets capitalized into higher home prices, the dollars needed for a down payment of say 10% doubles as the price of a home doubles. Yet as already noted, incomes (and savings) do not rise as quickly. At the start of the current home price boom in 2012, first-time FHA buyers had a median down payment of $3800. In January 2019 the median down payment was still $3800, yet the median home price purchased had increased by 31%. This translates into more risk.”

Just look at home prices compared to median household income:

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and our government-sponsored entities primarily exist to stimulate homeownership, and yet neither boasts a remarkable success rate at raising homeownership rates.

After the postwar homeownership boom from 44% in 1940 to 62% in 1960, homeownership rates have remained largely the same for a half a century, and that boom occurred before GSEs began securitizing mortgages and also before the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage became widely available (as you’ll recall from Part 1, the FHA didn’t offer TYFRMs in the private sector until the late 1950s).

Furthermore, we are pretty much one of the only developed nations with very-long-term fixed-rate mortgages and broad federal subsidies, and yet, our overall homeownership rate remains comparable to other countries that offer neither of those things.

It has long been said the correlation does not equal causation, but it can’t be entirely coincidental that as the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has increasingly dominated the market over the last several decades, homes have become less affordable, residential mortgage debt has skyrocketed, and homeownership rates have stagnated as home ownership becomes less sustainable.

The TYFRM is supposed to help Americans achieve the dream of homeownership, but the structure of our current market prevents that from happening, and the move to ease GSEs out of their government conservatorship presents an opportunity to work through some of these fundamental issues.

GSE reform: what now?

To summarize, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is popular because it’s what we’ve always favored, because borrowers have been told it’s the quickest way to build wealth, and because GSEs subsidize them to make them more attractive to lenders and investors by giving them a way to pass off the interest-rate risk (ultimately onto the American taxpayer).

We are the only country in the world to structure our mortgage finance system like this, and we should be asking ourselves why.

It’s a classic case of chicken and the egg: are we reliant on the thirty-year fixed-rate mortgage because the GSEs enabled them to become popular, or did GSEs just capitalize on our burgeoning obsession with 30-year mortgages and ride that out long past its prime?

With GSE reform on the horizon, we need to focus on reducing Fannie and Freddie’s market shart (GSEs bankroll about 45% of all residential mortgages as of 2018) and raise their capital requirements to prevent future economic downturns.

We need to focus on how to actually drive affordable housing rather than just calling an idealized mortgage product ‘affordable’ and calling it a day.

We need to take inspiration from other countries and develop a more robust set of products that better balances borrower, lender, and investor needs. One such product suggested by some economists and promoted by the NY Fed is the cost of funds indexed mortgage contract with government-backed catastrophic insurance (a.k.a. COFI-Cats) which you can read more about here and here.

And finally, we need to start viewing the 30-year mortgage as what it is: a mediocre mortgage product that has overstayed its welcome and prevented us all — borrowers, lenders, and investors — from realizing the true potential that lies beyond it.

** Much of the economic analysis and investor POV in this piece was informed by the thorough, thoughtful work of economist Byrne Hobart, as well as the extensive coverage of the 30-year mortgage and its relationship to GSE reform by experts Arnold Kling, Edward Pinto, and Alex Pollock who have done excellent work for AEI’s Housing Center. I am immensely grateful for their work on the topic.

____

<<< Read Part 2: Mortgage Products Around the World

<<< Read Part 1

Sources

“A Home of One’s Own.” Accessed September 25, 2019. https://www.nationalaffairs.com

“A Timeline of Mortgage History in the United States. | Brad L’Engle.” Accessed September 23, 2019. https://www.lenglemortgageprofessionals.com

Adams, Kristen. “Homeownership: American Dream or Illusion of Empowerment?” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, December 13, 2009. https://papers.ssrn.com

Almenberg, Johan, Annamaria Lusardi, Jenny Säve-Söderbergh, and Roine Vestman. “Attitudes Toward Debt and Debt Behavior.” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2018. https://doi.org

———. “Attitudes towards Debt and Debt Behaviour.” VoxEU.Org (blog), October 27, 2018. https://voxeu.org

“Alternative View: The Dutch Mortgage Market from an International Perspective.” Aegon AM. Accessed September 18, 2019. https://www.aegonassetmanagement.com

“You Have To Understand Germany’s Long-Standing Fear Of Debt.” Business Insider. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com

“Average Homeowners Stay 8 Years Before Moving.” Realtor Magazine, May 3, 2019. https://magazine.realtor

Badarinza, Cristian, John Y Campbell, Gaurav Kankanhalli, and Tarun Ramadorai. “International Mortgage Markets: Products and Institutions,” n.d., 15.

Bernhardsson, Erik. “Why I Went into the Mortgage Industry.” Erik Bernhardsson, February 17, 2017. https://erikbern.com

Buckley, Robert M. “Housing Finance in Developing Countries: The Role of Credible Contracts.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 42, no. 2 (1994): 317–32.

Burnett, Victoria. “A Job and No Mortgage for All in a Spanish Town.” The New York Times, May 25, 2009, sec. Europe. https://www.nytimes.com

“Don’t Let the 30-Year Mortgage Sway Housing Policy.” American Banker. Accessed September 25, 2019. https://www.americanbanker.com

Fabozzi, Frank J., and Franco Modigliani. Mortgage and Mortgage-Backed Securities Markets. Harvard Business School Press Series in Financial Services Management. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press, 1992.

Fernández de Lis, Santiago, Saifeddine Chaibi, Jose Félix Izquierdo, Félix Lores, Ana Rubio, and Jaime Zurita. “Some International Trends in the Regulation of Mortgage Markets: Implications for Spain.” Madrid, Spain: BBVA Research, April 2013. https://www.bbvaresearch.com

“From Main Street to King Abdullah Financial District: Lessons Learned in International Mortgage Finance.” RiskSpan – Data Made Beautiful (blog), July 12, 2018. https://riskspan.com

Green, Richard K, and Susan M Wachter. “The Housing Finance Revolution,” n.d., 47.

Gudell, Svenja. “A Glimpse at Life Without the 30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgage.” Forbes. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.forbes.com

“Here’s How Muslim Buyers Get around the Mortgage Interest Problem—but It’s Tough in NYC.” Brick Underground, February 22, 2017. https://www.brickunderground.com/buy/muslim-friendly-mortgages.

Hobart, Byrne. “The 30-Year Mortgage Is an Intrinsically Toxic Product.” Medium, January 18, 2019. https://medium.com

“Housing Finance Fact or Fiction? FHA Pioneered the 30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage during the Great Depression?” AEI, June 24, 2015. http://www.aei.org

“Https://Www.Aei.Org/Economics/5-Mythical-Benefits-of-Gses/.” American Enterprise Institute – AEI (blog), June 18, 2013. https://www.aei.org/economics/5-mythical-benefits-of-gses/.

“Https://Www.Aei.Org/Economics/Bernanke-Gses-Arent-Necessary-to-Support-Homeownership/.” American Enterprise Institute – AEI (blog), June 20, 2013. https://www.aei.org

“In China, a Three-Digit Score Could Dictate Your Place in Society.” Wired. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.wired.com

Kagan, Julia. “Balloon Mortgage.” Investopedia. Accessed September 23, 2019. https://www.investopedia.com

Maranjian, Selena. “4 Reasons to Avoid a 30-Year Mortgage at All Costs.” The Motley Fool, March 14, 2017. https://www.fool.com

McLean, Bethany. “Opinion | Who Wants a 30-Year Mortgage?” The New York Times, January 5, 2011, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com

“Mortgage Loans Around the World.” The Finance Buff, September 29, 2008. https://thefinancebuff.com

“New Bubble May Be Building in 30-Year Mortgages.” AEI, December 23, 2011. http://www.aei.org

“New Bubble May Be Building in 30-Year Mortgages | AEI.” American Enterprise Institute – AEI (blog). Accessed September 25, 2019. https://www.aei.org

Nguyen, Jeremy, Abbas Valadkhani, and Russell Smyth. “Mortgage Product Diversity: Responding to Consumer Demand or Protecting Lender Profit? An Asymmetric Panel Analysis.” Applied Economics 50 (July 21, 2018): 4694–4704. https://doi.org

Osborne, Hilary. “Islamic Finance – the Lowdown on Sharia-Compliant Money.” The Guardian, October 29, 2013, sec. Money. https://www.theguardian.com

Parrott, Jim, Lew Ranieri, Gene Sperling, Mark Zandi, and Barry Zigas. “A More Promising Road to GSE Reform,” n.d., 11.

“(PDF) Mortgage Product Diversity: Responding to Consumer Demand or Protecting Lender Profit? An Asymmetric Panel Analysis.” Accessed September 18, 2019. https://www.researchgate.net

Rodima-Taylor, Daivi, and Parker Shipton. “BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAND MORTGAGE WORKING GROUP RESEARCH REPORT • 03/2017,” n.d., 72.

Rodríguez-Planas, Núria. “Mortgage Finance and Culture.” Journal of Regional Science 58, no. 4 (September 2018): 786–821. https://doi.org

Scanlon, Kathleen, Jens Lunde, and Christine Whitehead. “Mortgage Product Innovation in Advanced Economies: More Choice, More Risk.” European Journal of Housing Policy 8, no. 2 (June 3, 2008): 109–31. https://doi.org

Stoykova, Polina, and Linjie Chou. “Housing Prices and Cultural Values : A Cross-Nation Empirical Analysis,” 2013.

“The 30-Year Fixed Mortgage Should Disappear.” AEI, April 26, 2016. http://www.aei.org

“The Challenge of Building Affordable Housing in Developing Countries … and How DFIs Can Help | OPIC : Overseas Private Investment Corporation.” Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.opic.gov

“The Risky Mortgage Business: The Problem with the 30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgage.” AEI, December 11, 2012. http://www.aei.org

“Untangling the GSE Mess.” Scotsman Guide Media. Accessed September 25, 2019. /Residential/Articles/2019/03/Untangling-the-GSE-Mess/.

“What’s So Special about the 30-Year Mortgage?” AEI, February 1, 2011. http://www.aei.org

“Why Do We Have a 30-Year Mortgage, Anyway?” Marketplace (blog), October 31, 2018. https://www.marketplace.org/2018/10/31/why-do-we-have-30-year-mortgage-anyway/.

“Why the Universal Use of the 30-Year Mortgage Is Dangerous.” AEI, April 22, 2019. http://www.aei.org

by Chelsea Mize

We are ready to help you find the best possible mortgage solution for your situation. Contact Sheila Siegel at Synergy Financial Group today.